The Rebirth

of a Legend

History of Britannia

The royal cutter yacht Britannia was built by Henderson’s on the Clyde in 1893 for Queen Victoria’s son Albert Edward, then Prince of Wales. George Lennox Watson designed her to the Length and Sail Area Rule and had her constructed at the D&W Henderson Yard on the River Clyde in Scotland.

Built of wooden planking over steel frames in little more than four months, she was launched on 20 April 1893. The time frame may have been impossibly fast by today’s standards but designer and builder alike made a fine job of Britannia.

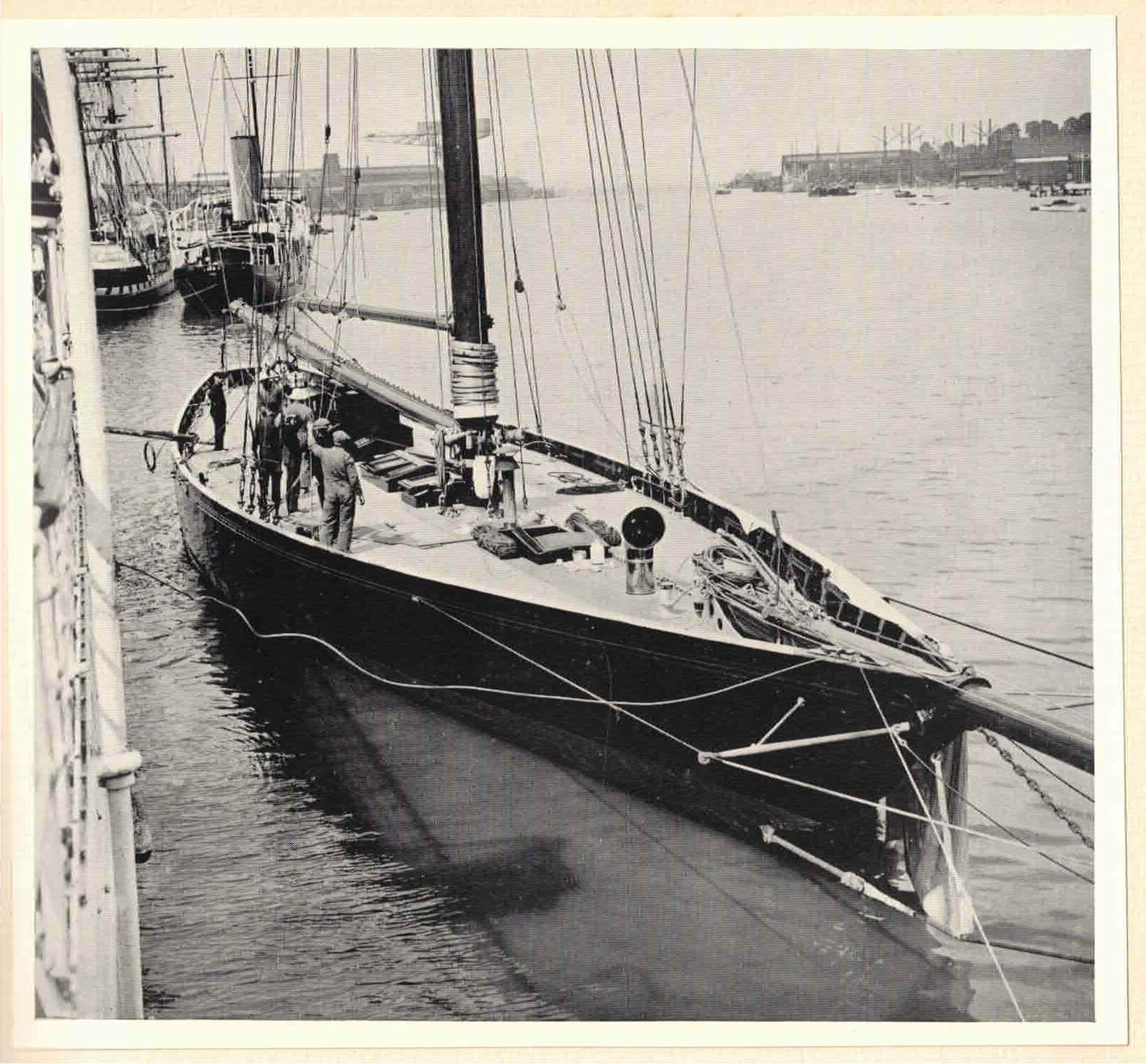

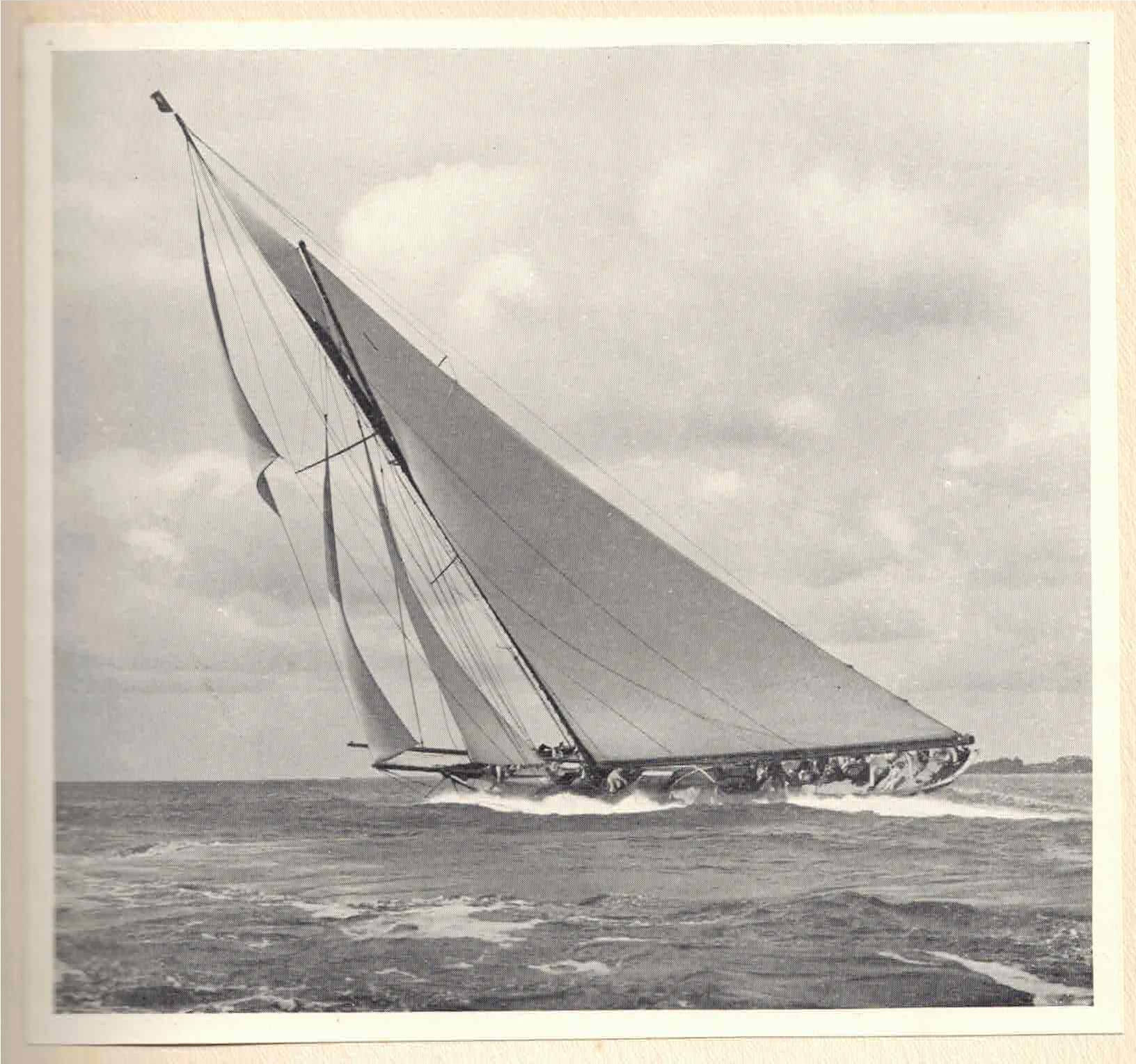

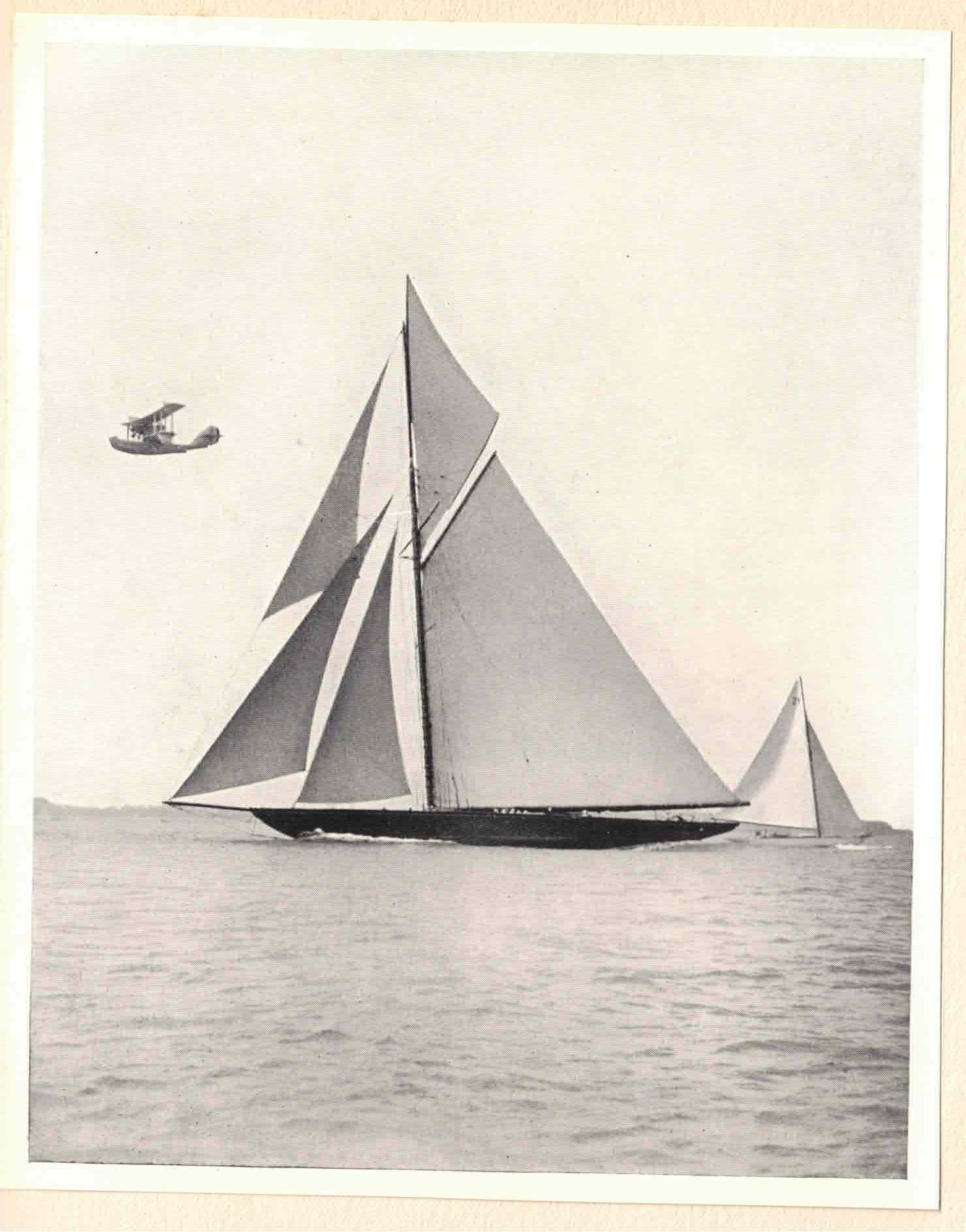

The black-hulled beauty was exceptionally fast as well as stunning to look at. Moved down to Cowes, which she would call her home port for the next four decades, a top racing crew was assembled as Britannia was put through her paces in and around the Solent.

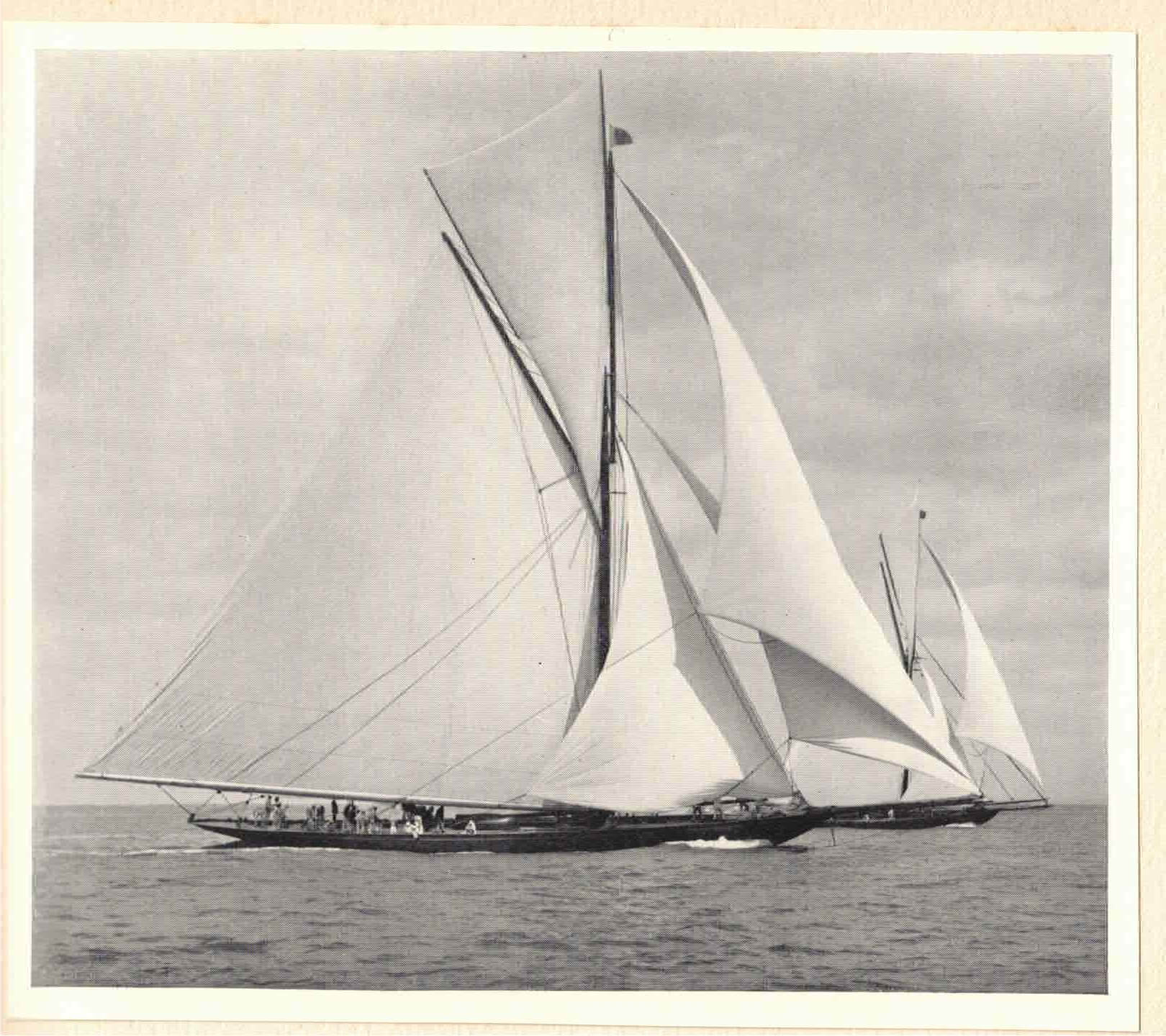

In her first season of racing, she scored 24 wins in 43 starts, as well as nine other prizes. In 1894 Britannia won all seven races for the ‘Big Class’ yachts on the French Riviera, then beat the 1893 America’s Cup defender Vigilant in home waters. The next three years were equally successful, with another 86 prizes to her name.

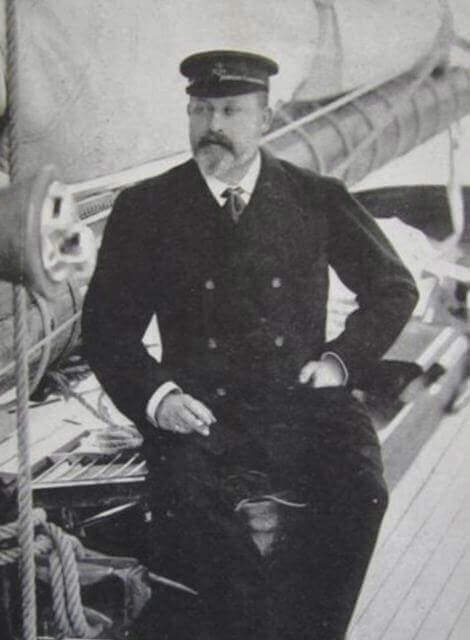

During the years leading up to World War I, Britannia was used mainly for cruising by King Edward VII and then, after his death in 1910, by his son and heir King George V.

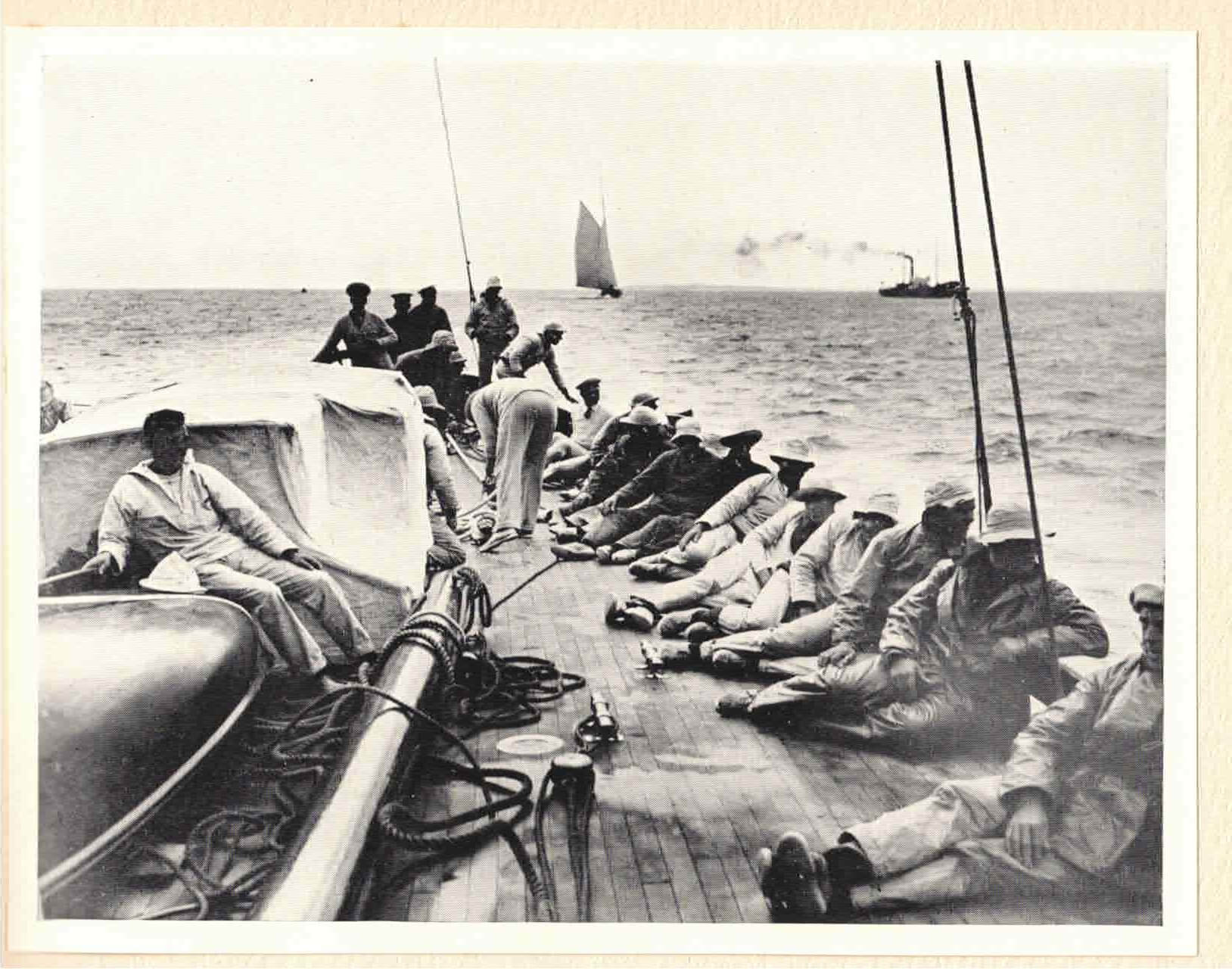

While Britannia is famed for her racing exploits, she was also a beautiful boat on which to relax and many contemporaries told stories of their time onboard. If her elegant exterior profile transfixed the eye of observers from afar, those lucky few who got to spend time on and below her decks never forgot the experience.

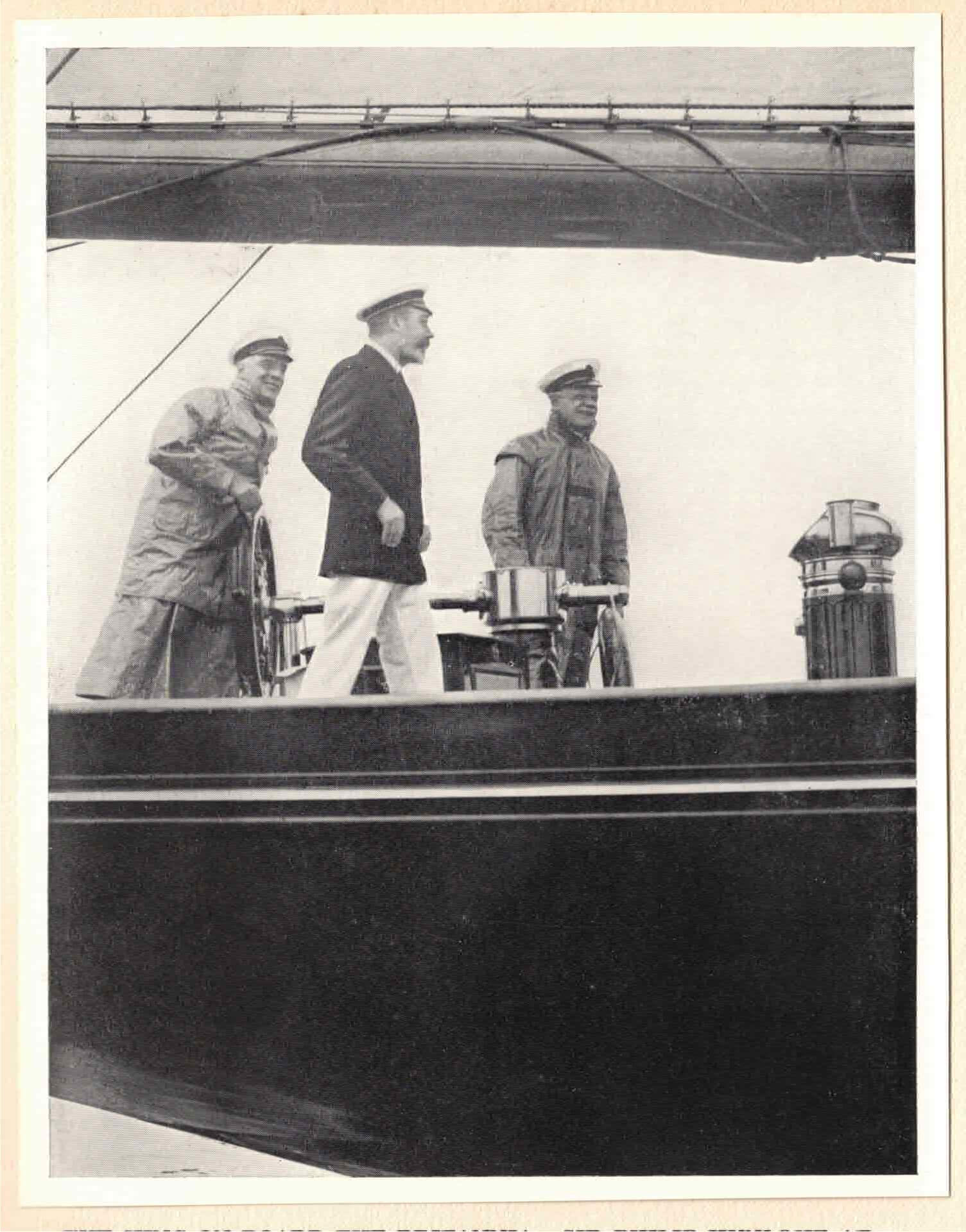

Two years after the end of what was then dubbed ‘the war to end all wars’ (if only), King George V felt that the nation needed a boost. He triggered the revival of the Big Class by announcing that he would refit Britannia for racing.

Many yacht owners took up the gauntlet, including Herbert Weld who had the beautiful Lulworth built especially to race against Britannia. Although Britannia was the oldest yacht in the circuit, regular updates to her rig made her one of the most successful racers throughout the 1920s.

The Big Class revival initiated by Britannia was one of the key reasons for the immergence of the J-class yachts, built with only one mast to the Universal Rule. Five were launched in 1930 in the UK and US, namely Enterprise, Shamrock V, Weetamoe, Whirlwind and Yankee.

Never one to resist a sailing challenge, King George commissioned a major refit for Britannia in 1931 that gave her a Bermudan rig. The legendary Charles E Nicholson designed the tallest wooden mast the world has ever seen: made of silver spruce, it weighed an incredible three tons.

A rejuvenated Britannia went on to add 15 more firsts to her record during her final years, giving her a grand final total of 231 wins out of 635 races. Her last hurrah came in the summer of 1935 as she raced against the American J Class Yankee in British waters.

career

places

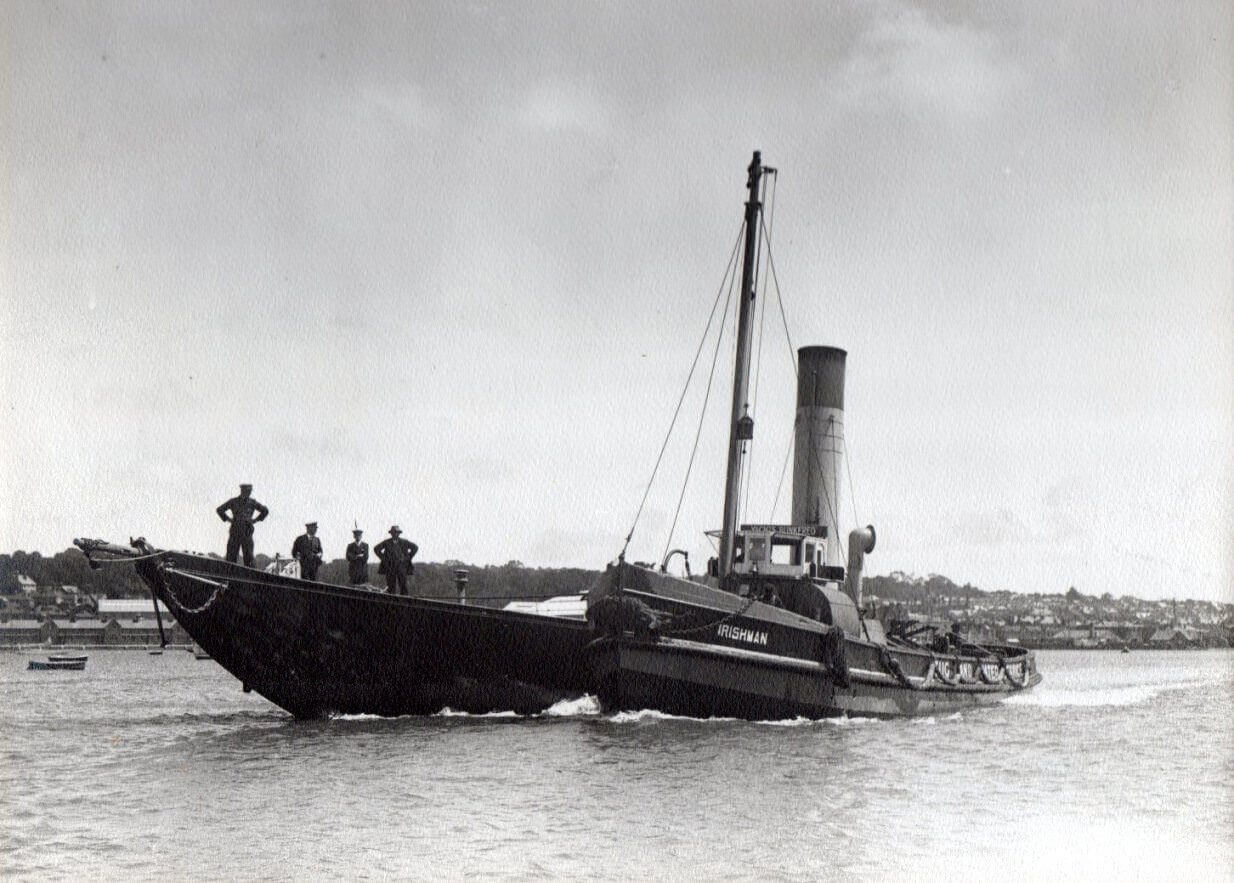

In January 1936 the British people mourned the passing of King George V. It was announced that in accordance with the monarch’s wishes upon his death, Britannia would be stripped of her spars and fittings and scuttled.

On 10 July 1936 her hull was picked up by HMS Winchester and towed out to St. Catherine’s Deep near the Isle of Wight. There she was scuttled and laid to rest beneath the waves, with a simple garland of flowers placed on her stem-head.

Norwegian entrepreneur Sigurd Coates decided to follow a long-cherished wish and began construction of a replica of Britannia at the Solombala shipyard in Archangel, Russia. “It started with a dream and following your dreams is a big part of life,” he says at the time.

The project then became a labour of love taking 11 years to complete and involved seven nationalities. Using the original drawings from Scotland, Sigurd and his team recreated the hull in pine wood with a laminated oak frame.

Although the boat was ready to launch for outfitting in 2005, Britannia became enmeshed in a legal minefield in Russia for another five years. By the time Sigurd was finally able to take possession of his Britannia in 2009 and move her to Norway for completion, the global recession had taken its toll financially.

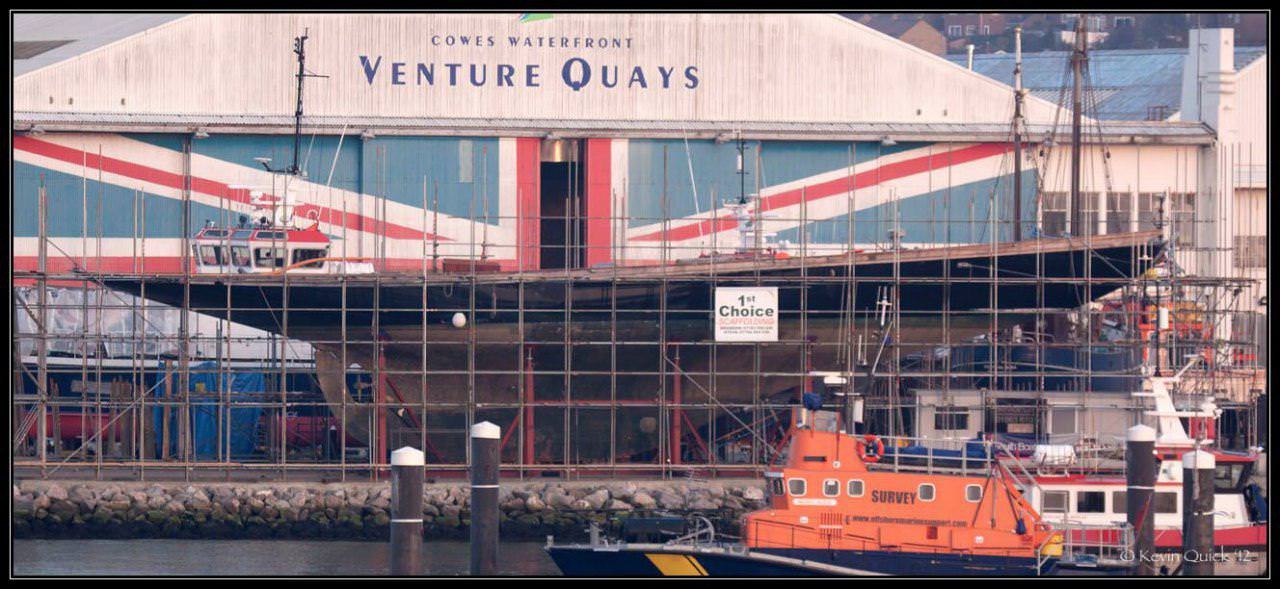

Realizing the difficulty of completing the project, Sigurd was inspired by the ideas of the K1 Britannia Trust to use the boat as a flagship for charity, and agreed to sell her. The hull was transported to Cowes and taken out of the water at the Southboats yard. K1 invested in the scaffolding, cradle, tools and workmen required and rebuilding work resumed in earnest on the next stages of the Britannia build.

The Southboats yard was liquidated and all building work stopped. Britannia was placed back in the water. Over the next couple of years, various surveyors carefully inspected Britannia and a full scope of the work for continuing the rebuild was undertaken.

The K1 team decided to broaden its thinking as to the best type of replica and how they could fulfill the purpose of Britannia while ensuring Britannia’s relevance and stature in the modern sailing world. Based on research, and in the interest of sustainability, the Trust decided to follow the vision of GL Watson while also maximizing the best technology available to boat builders today